©Tous droits réservés

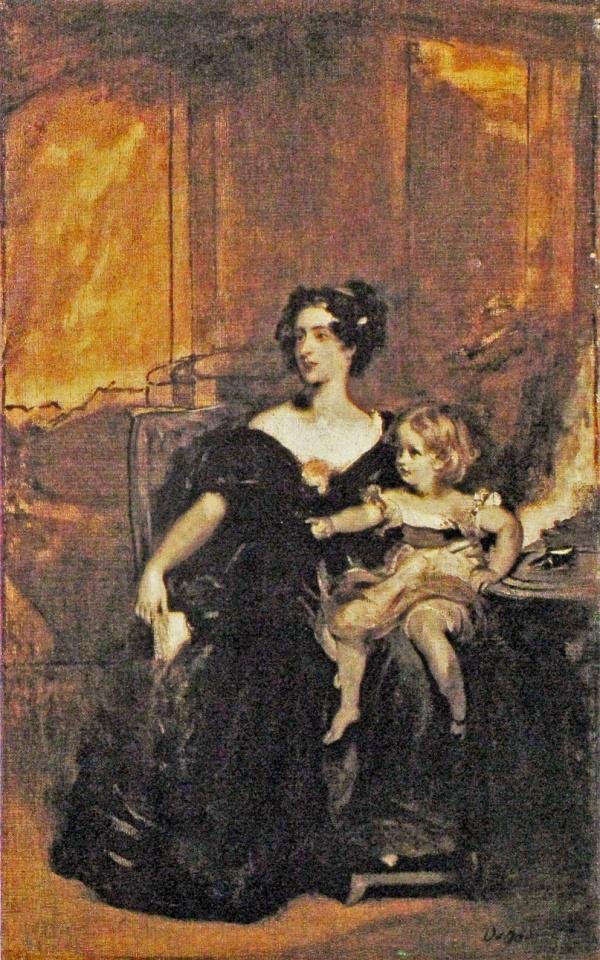

Portrait de Lady Gower et de sa fille

[Portrait of Lady Gower and Her Daughter]

MS : 39

- Localisation

- Collection particulière

L'œuvre

- Dimensions

- 68 × 43 cm - 26 3/4 × 16 15/16 in.

- Période

- Circa 1869

- Médium

- Huile

- Support

- toile

- Signature

- en bas à droite : Degas

Informations additionnelles

Historique

Durand-Ruel & Cie, Paris – Vente Sotheby’s, Londres, 5 décembre 1979, n° 10 – Vente Sotheby’s, Londres, 2 avril 1981, n° 308 – Collection particulière.

Bibliographie

Grappe, "Degas", L’Art et le Beau, [1908], repr. p. 39 – Meier-Graefe, 1923, pl. X – George, «Sur quelques copies de Degas», La Renaissance de l'art français et des industies de luxe, janvier-février 1936, n° 1-2, p. 8 (repr.) – Lemoisne, 1946-1949, II, n° 189, repr. p. 101 – Lassaigne, Minervino, 1974, n° 56, repr. p. 98 - Loyrette, Degas, 1991, p. 598.

Dernière mise à jour : 21/08/2025