Peintures

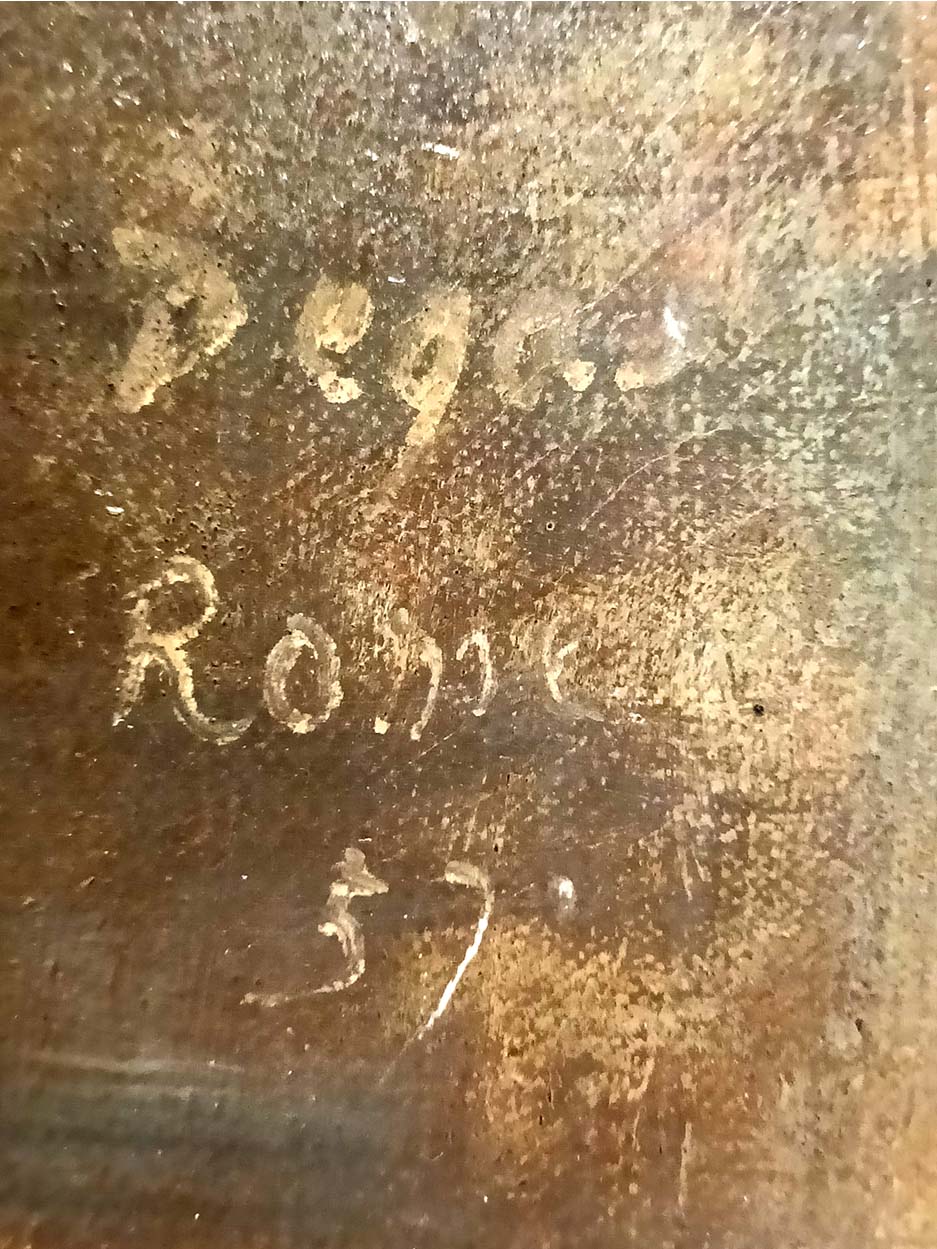

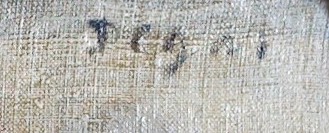

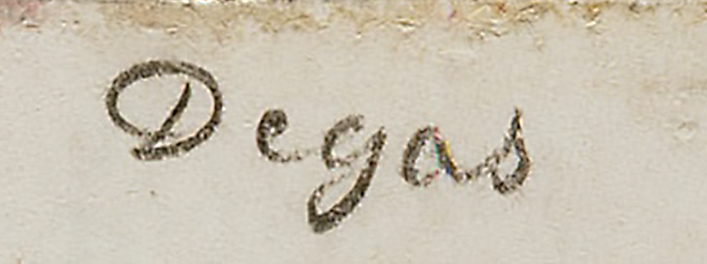

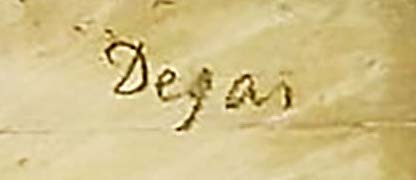

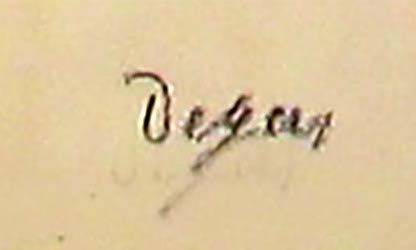

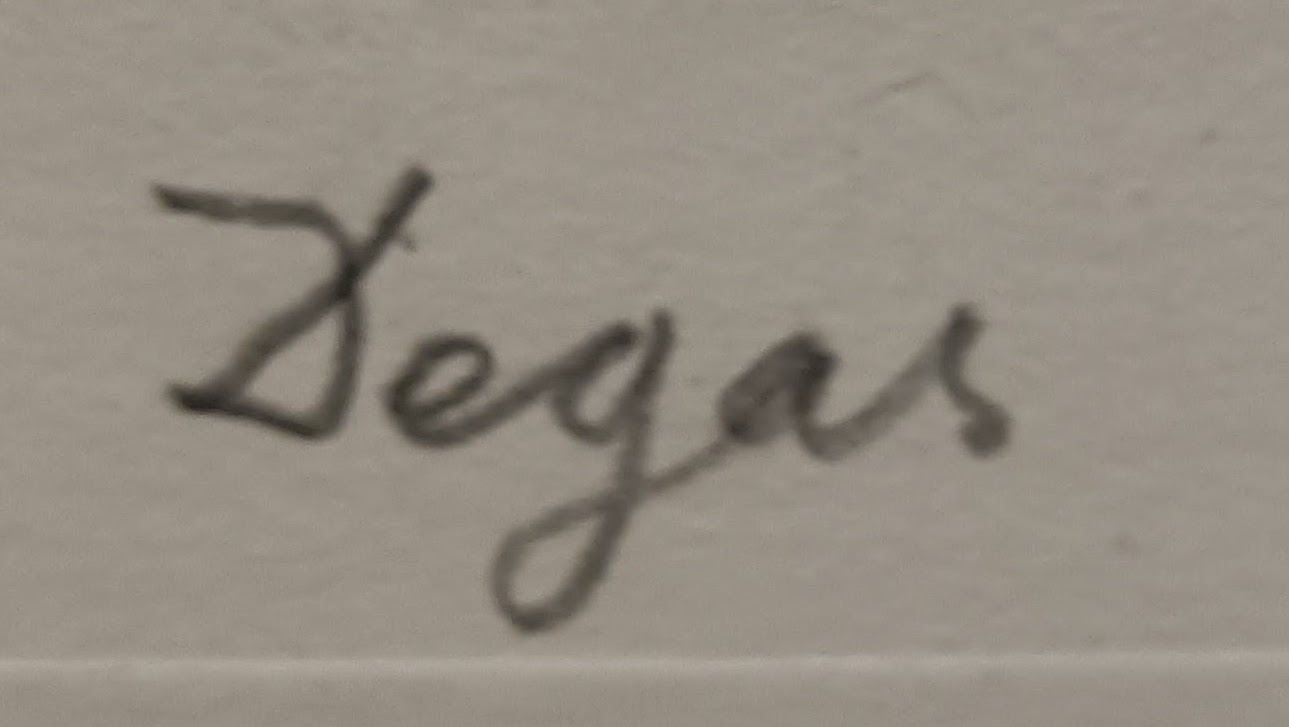

- Signé et daté en haut à gauche : Degas Rome 57

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-887

Une des premières peintures de Degas signée, datée et localisée où domine l’épaisseur du trait du pinceau qu’on retrouvera ultérieurement dans d'autres œuvres de Degas. On remarquera la forme particulière du R ainsi que la toile sous-jacente.

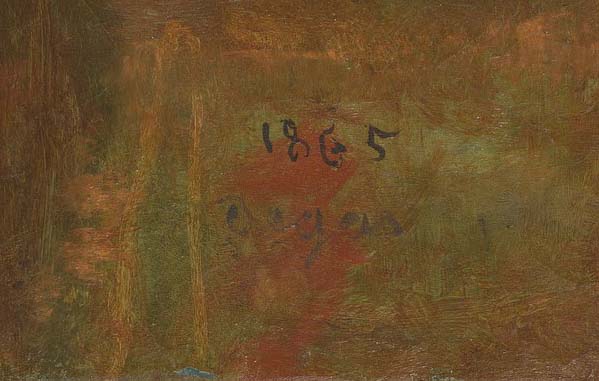

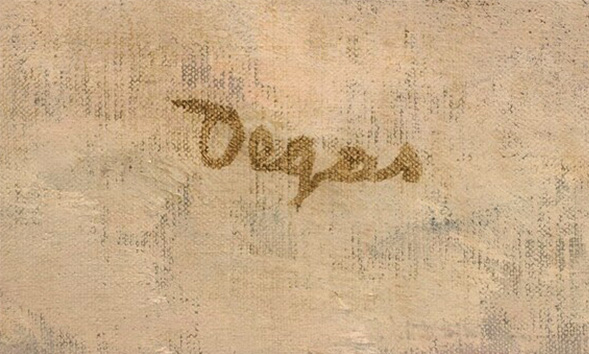

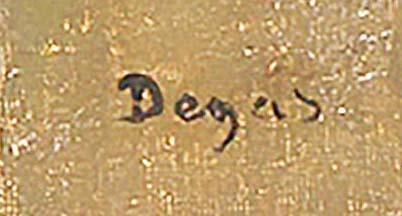

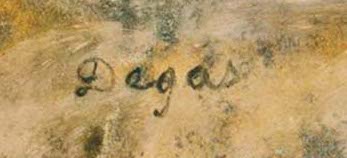

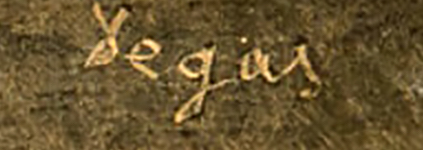

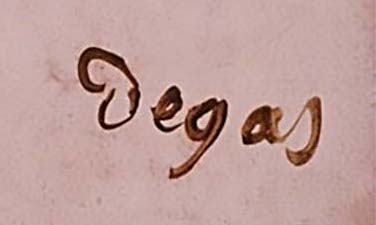

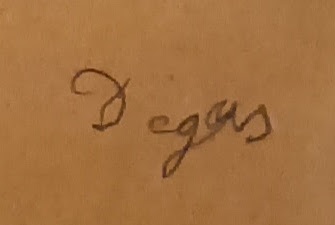

- Signé et daté en bas à gauche : Degas 1865

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-818

Sur l’un des plus célèbres tableaux de Degas, cette date très lisible s’oppose à une signature légèrement apposée ou peut-être abusivement nettoyée et donc en partie effacée. La date ressort davantage que la signature si bien qu’on pourrait croire qu’elle a été rehaussée. Ce que nous ne pensons pas. En tous les cas, la forme du D s’éloigne nettement de celle de La Vieille Italienne.

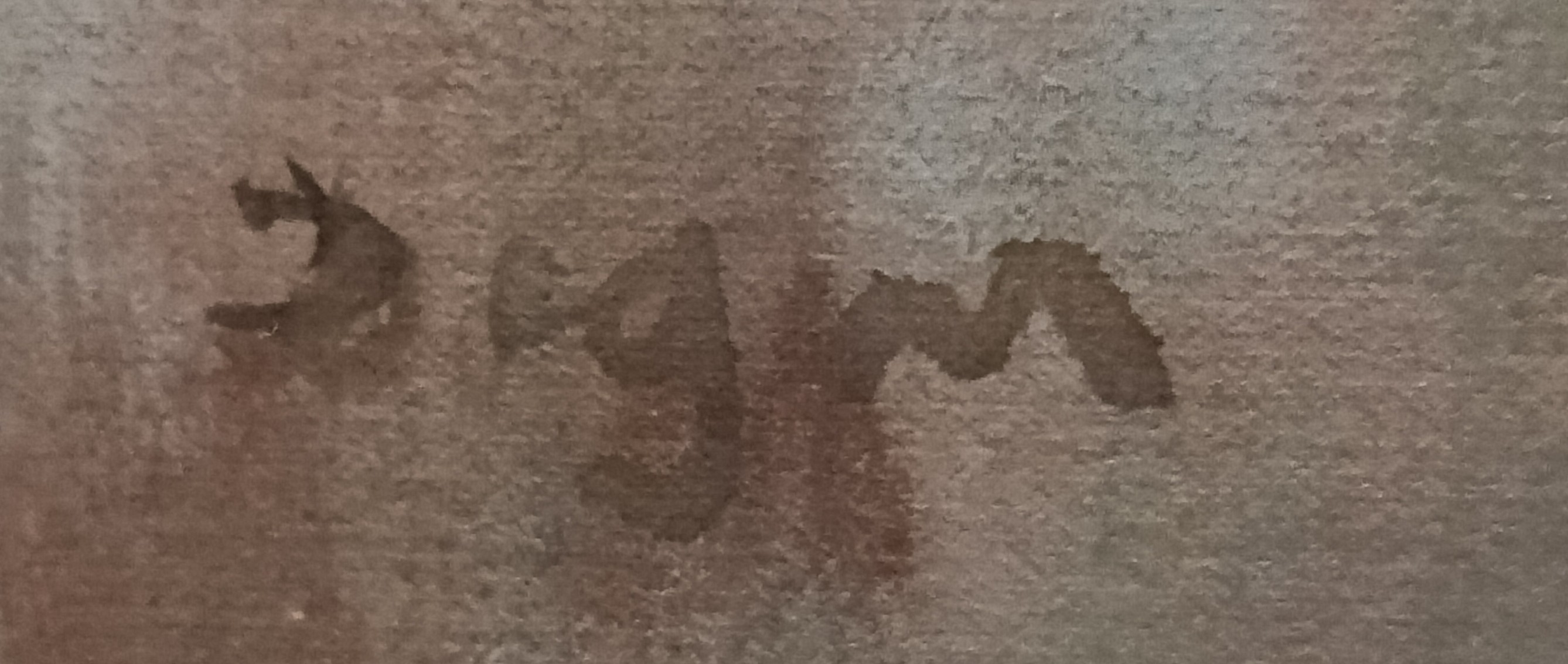

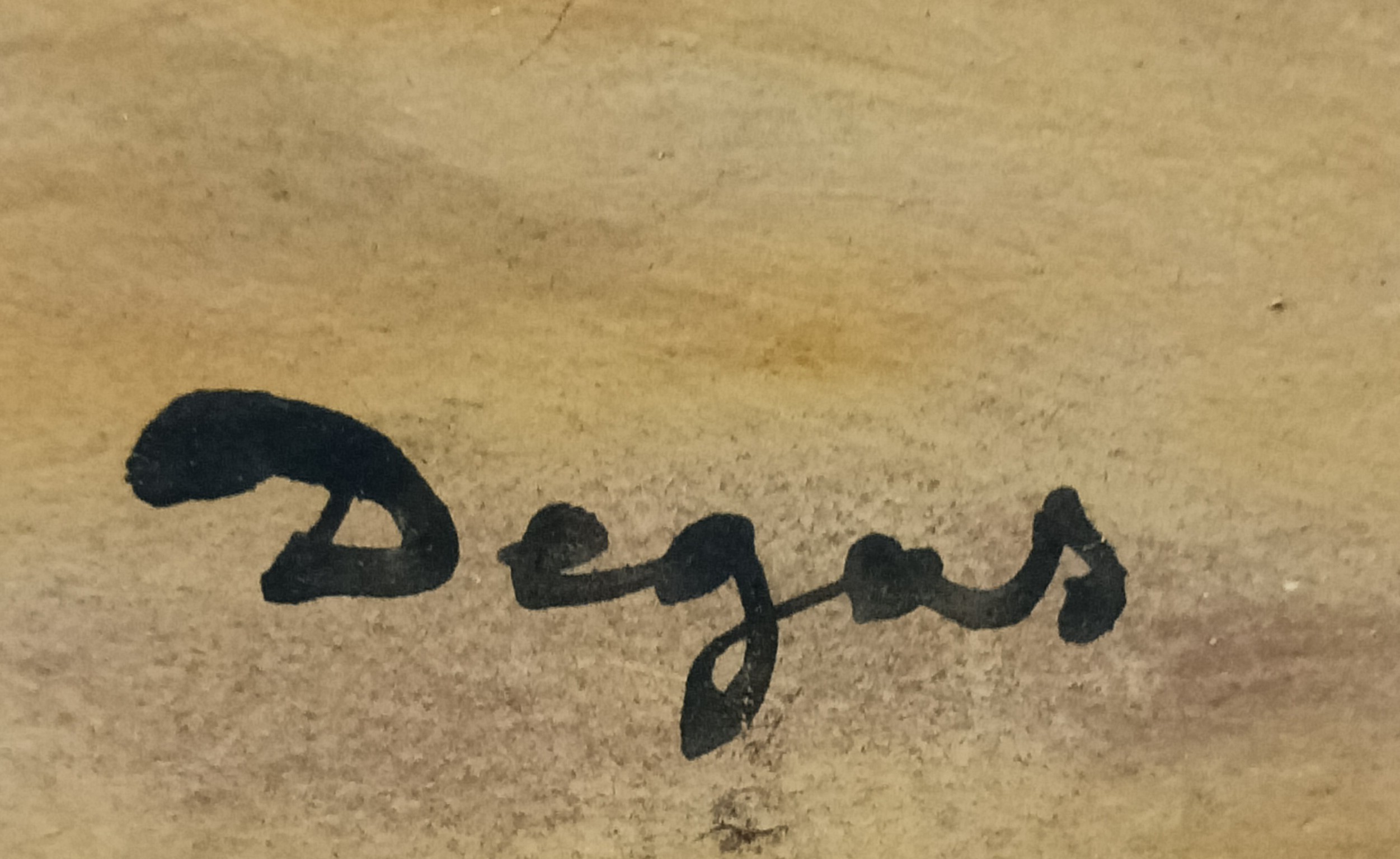

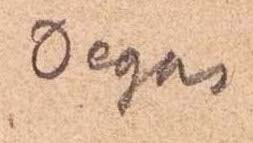

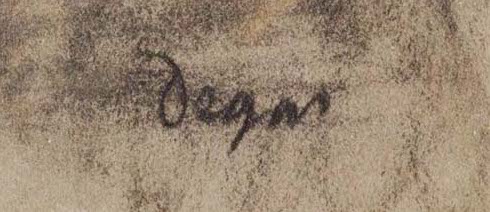

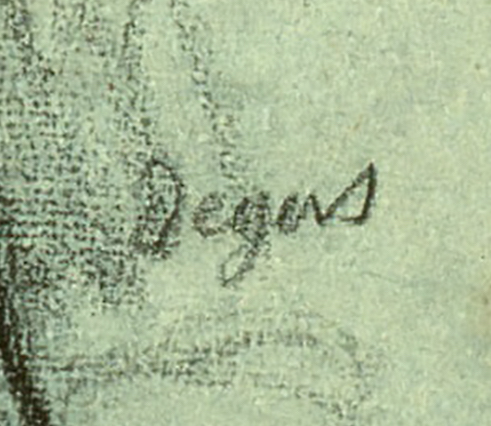

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-56

Apposée sur papier, cette signature fait penser à de l’aquarelle. Elle semble avoir été absorbée par le papier contrairement aux signatures à l’huile. D’où, ici, toute l’importance du support papier.

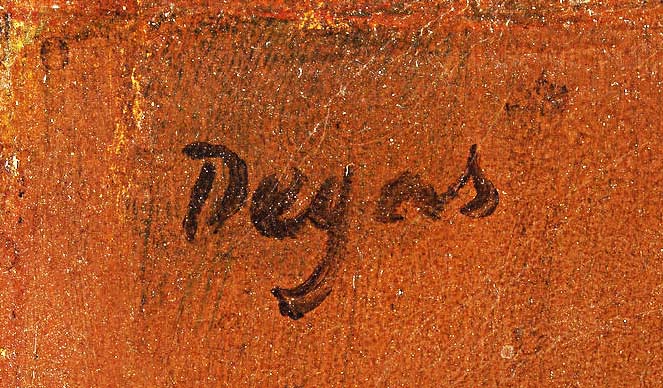

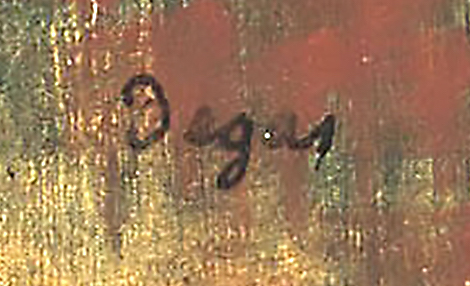

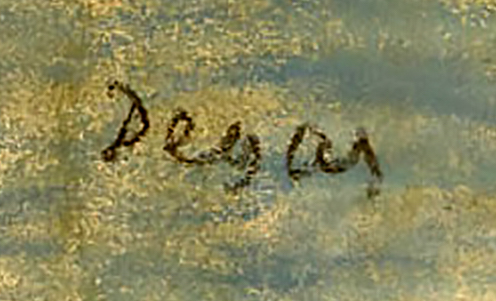

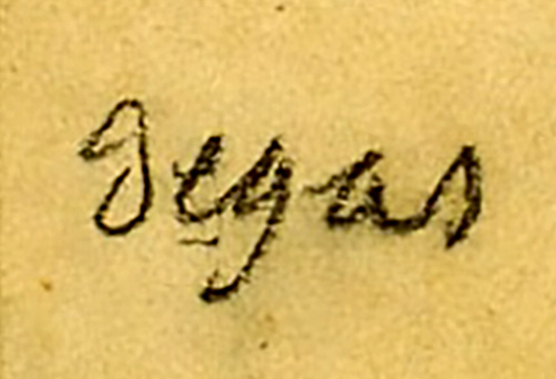

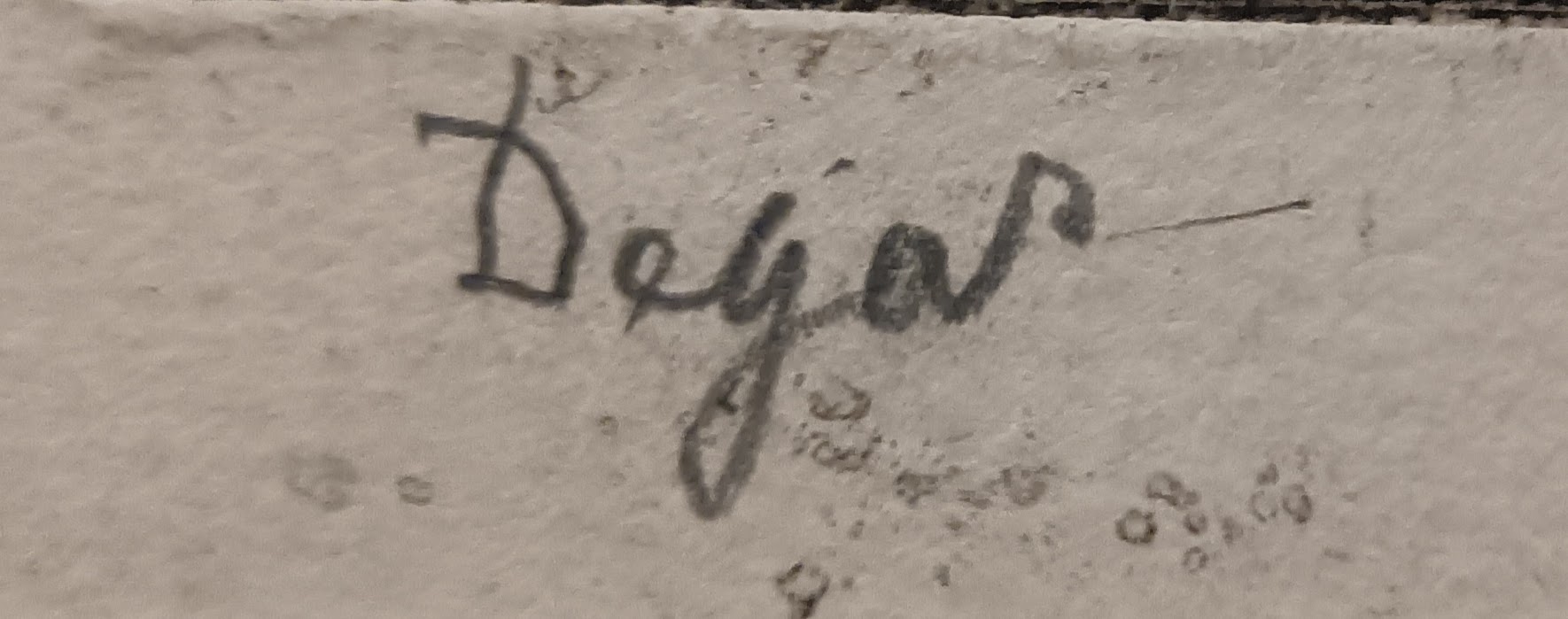

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1899

Une signature au pinceau à l’huile dont le graphisme est comparable à celui de La Vieille Italienne avec néanmoins une sensible différence concernant la forme de la lettre D.

- Signé et daté en bas à gauche : Degas 1868

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-852

Discrètement apposée en bas à gauche, cette signature, ton sur ton, est à peine lisible. On discerne plus distinctement la date de 1868 contrairement à 1866 comme le propose le Metropolitan Museum of Art.

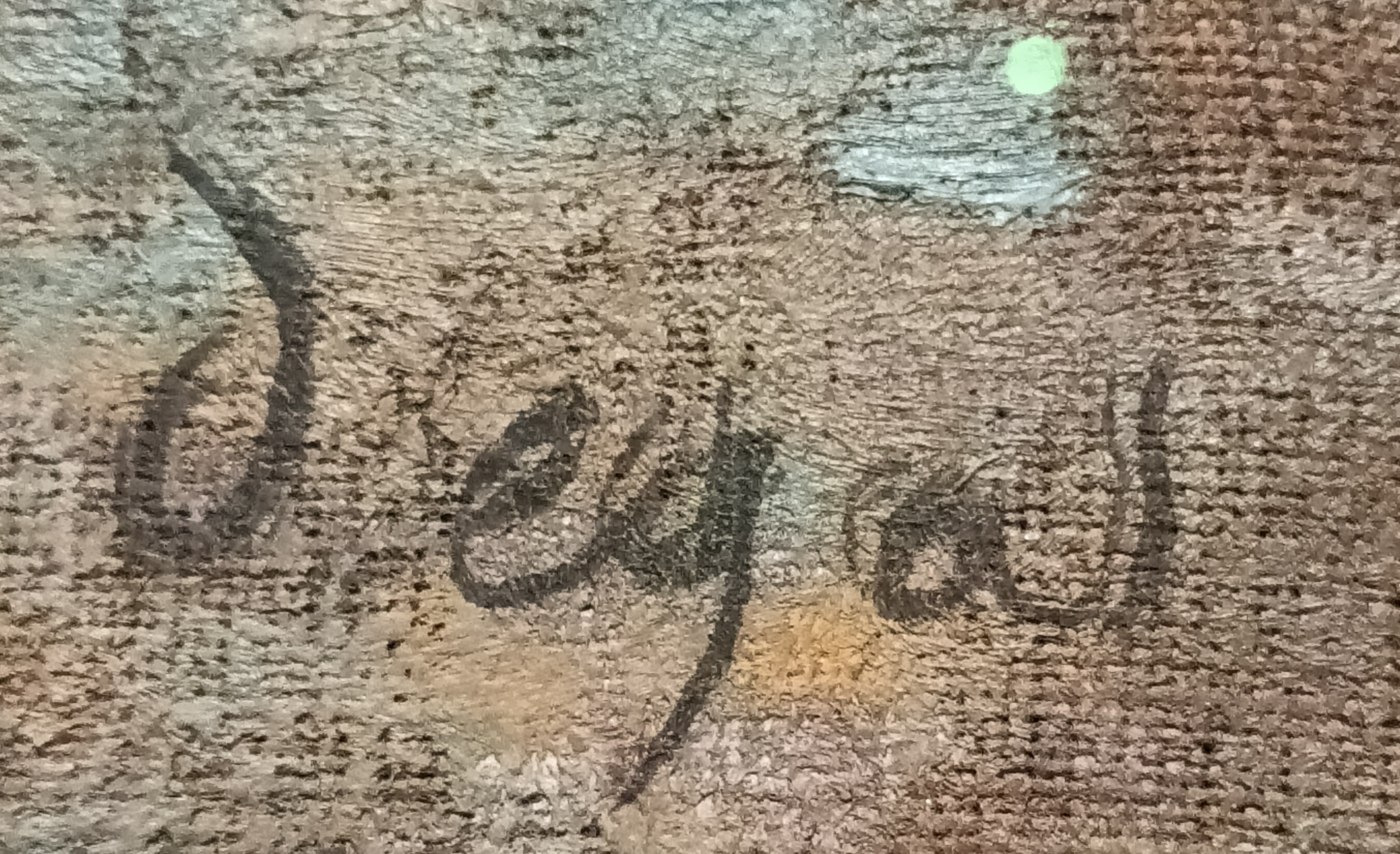

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-795

Cette signature au pinceau se distingue des précédentes par la forme originale du D et celle du G qui sont peu communes chez Degas. La signature en noir sur fond beige la fait particulièrement bien ressortir.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Yale University Art Gallery - New Haven

- MS-99

Visiblement signée en bas à droite, cette œuvre est la première vendue aux enchères à Paris le 13 janvier 1874, n° 18. La signature du haut est en partie effacée mais c’est la seconde à gauche qui retiendra notre attention par l’originalité du graphisme du E et de celui du D. Cette signature apparaît rarement chez Degas mais est bel et bien authentique. On est en droit de supposer que le graphisme, notamment du E, s’est inspiré de la carte de visite manuscrite de Degas (voir ci-contre).

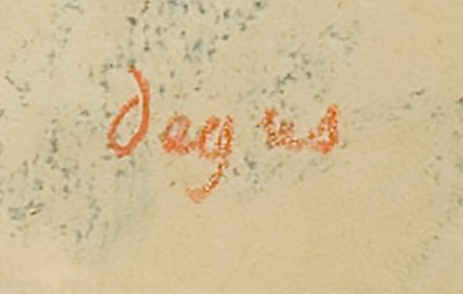

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1642

Le tableau rend bien la couleur crème du sol et de ses rayures qui font ressortir la signature rouge. On s’intéressera, là encore, à la forme originale du D et du G.

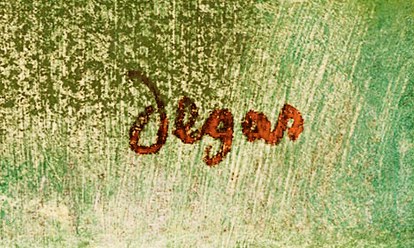

- Signé et daté en bas à droite : Degas 71

- National Gallery of Art - Washington

- MS-2076

Peut-êttre exécuté lors d’un séjour en Normandie, ce tableau évoque la passion de Degas pour les chevaux. Cette scène attendrissante ne nous étonnera donc pas. Quant à la signature, elle est particulièrement inhabituelle et ne manque pas d’originalité. On décrypte sans hésiter le E, sans doute inspiré des cartes de visites de Degas à cette époque ainsi que le reste marron qui ressort parfaitement sur le fond vert. On remarquera les espaces entre le E du prénom et Degas ainsi que celui entre le nom et la date. Le grain de la toile est très visible.

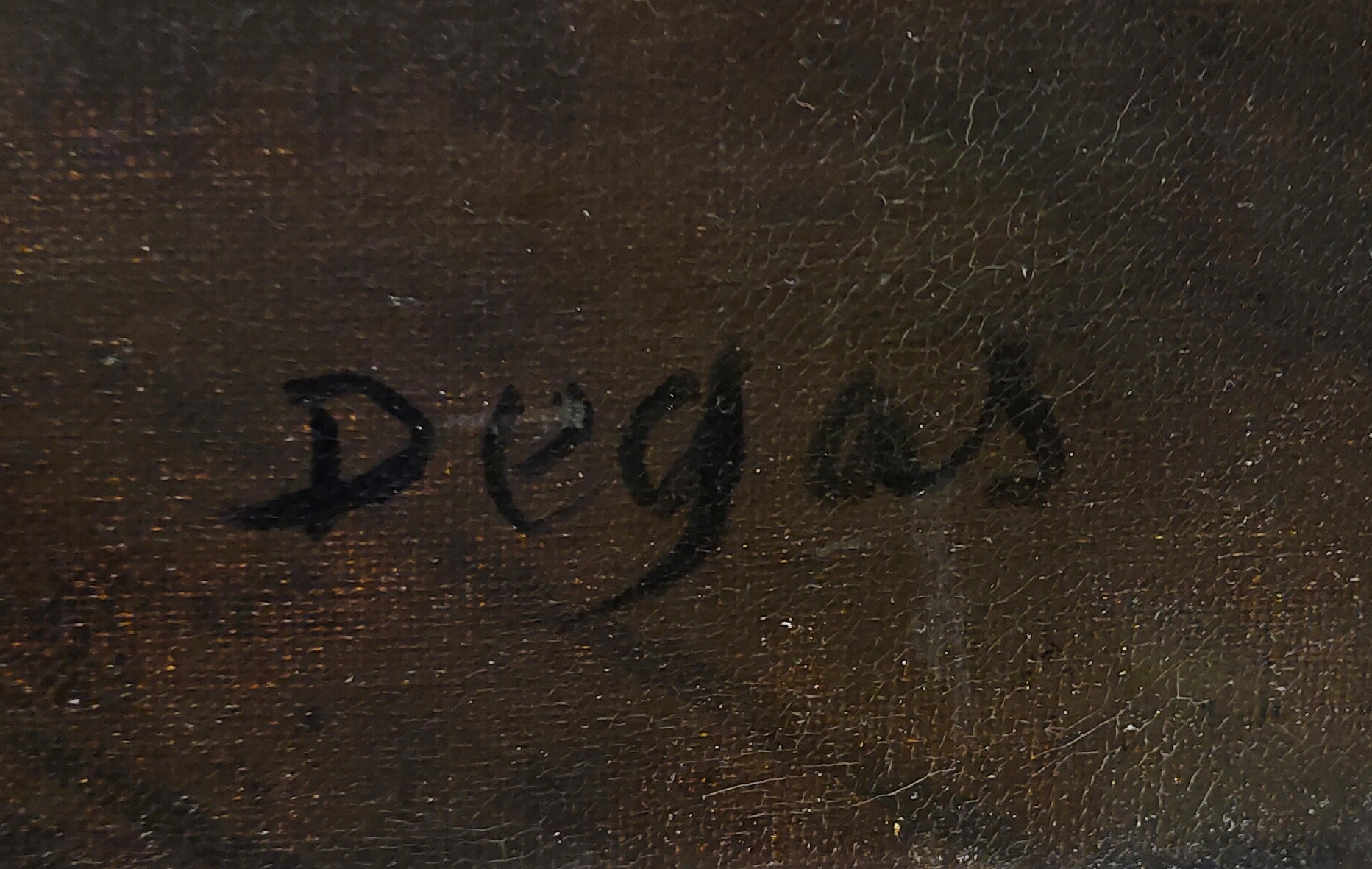

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-583

On distingue à peine la signature marron située approximativement à mi-distance entre la main de la repasseuse et le bord de la toile. Etrange signature apposée sur la toile dont on déchiffre à peine le D, le G et le A avec le S totalement effacé. Cette signature a-t-elle été abrasée par un nettoyage trop vigoureux ? C’est en tout cas la réponse que nous pouvons logiquement apporter concernant cette signature à peine lisible et déchiffrable.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Norton Simon Museum - Pasadena

- MS-1953

Cette signature sur toile reprend la couleur gris-jaune de certaines parties du tableau. Hormis le D et le g, on notera l’originalité du s, l’ensemble faisant penser à une signature à l’aquarelle.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Ordrupgaard - Copenhague

- MS-1156

Signé en noir sur panneau, le tableau a été exécuté pendant le séjour de Degas fin 1872-début 1873 à La Nouvelle Orléans. La signature ressemble à d’autres de la même époque dont on remarque la forme ample et originale du D ainsi que celle du G et du S final.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian - Lisbonne

- MS-1414

La signature en noir apparaît derrière le dossier du fauteuil sur lequel est posée une palette de peintre. Elle ressemble à la signature du Ordrupgaard de Copenhague mais s’en distingue néanmoins par la forme du D que Degas utilise assez souvent de façon variée, c’est-à-dire sans véritable constante graphique.

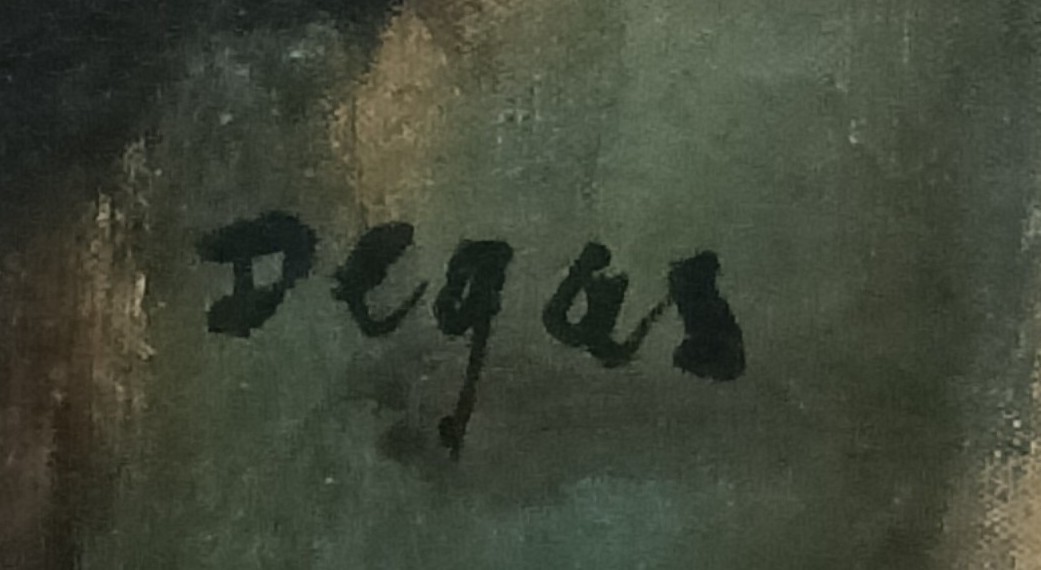

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1263

Célèbre tableau notamment pour l’originalité de la mise en page du sujet dont la signature se perd dans la partie sombre en bas à droite. On remarquera que le pinceau n'a pas terminé le D ainsi que la forme inhabituelle du s. Ce n’est d’ailleurs pas l’unique fois que la signature de Degas se termine ainsi.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-864

La signature est ici traditionnelle. Le tableau étant une huile sur toile, on pourrait néanmoins penser à la signature d’un pastel ou d'un dessin dont elle imite les formes. Le D recourbé dans le haut a sans doute inspiré les concepteurs du cachet des ventes posthumes de 1918 et 1919.

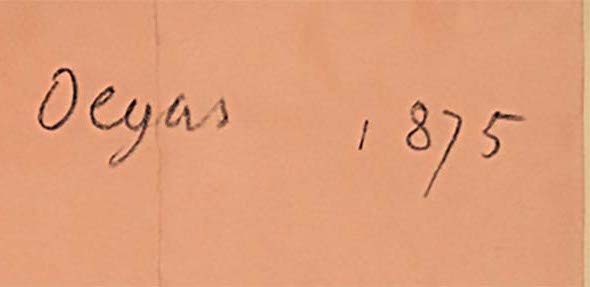

- Signé et daté en haut à droite : Degas 1875

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1961

On doit très certainement la finesse de la signature au papier sur lequel Degas l'a apposée tout comme la date de 1875. Elle a très probablement été faite au crayon.

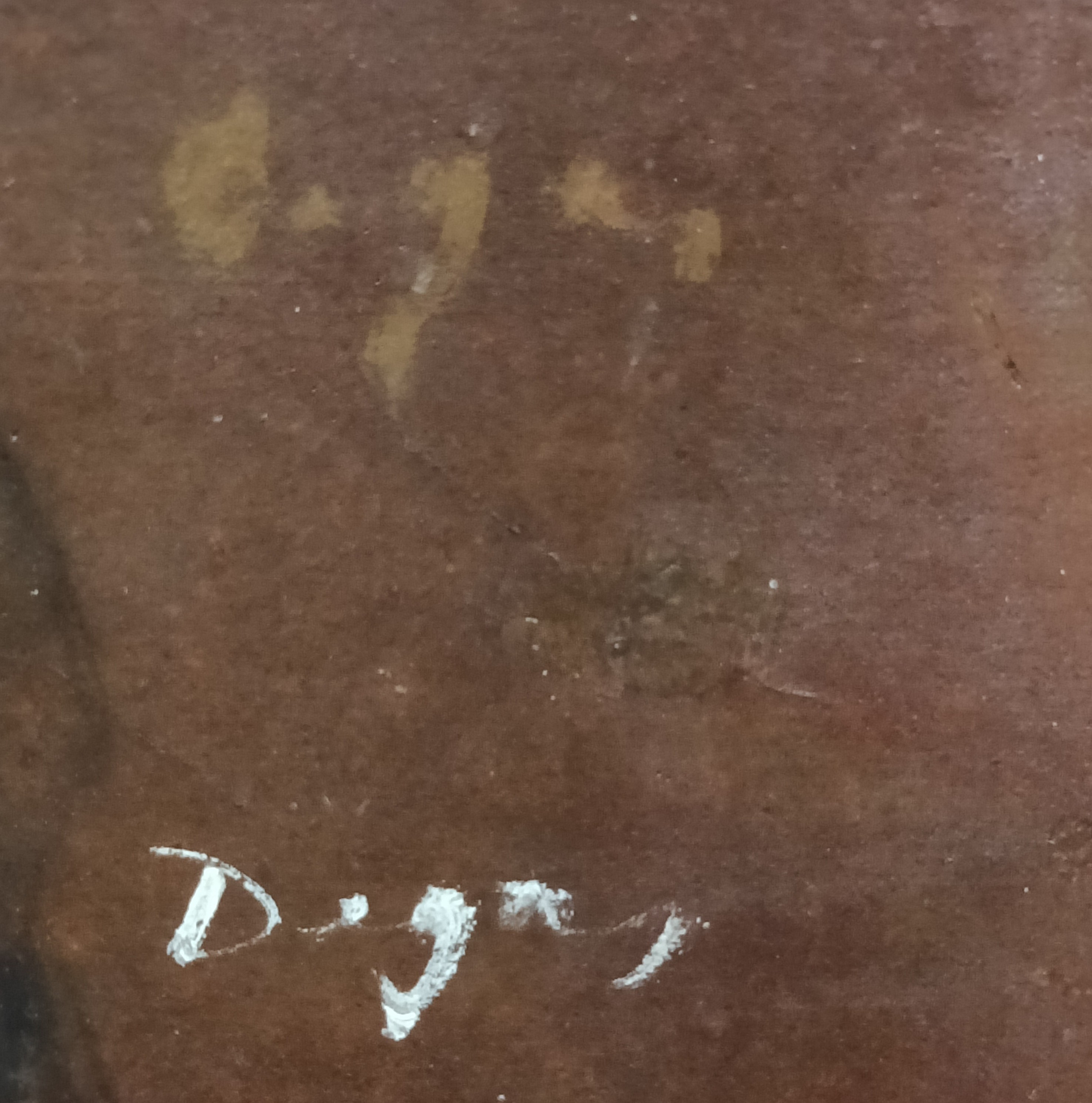

- Signé 2 fois en bas à droite : Degas

- Dresde, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

- MS-90

Il existe plusieurs versions de la Femme aux jumelles, Degas vouant une passion pour l’opéra. Exécutée à l’huile ou à l’essence directement sur carton, cette signature ressort par ses contrastes entre les blancs et les bruns. Le tableau est doublement signé en bas à droite. La signature du haut est à peine visible. C’est sans doute pourquoi Degas l’a reprise plus bas dont l’originalité ne nous échappera pas. Le blanc éclate sur le fond marron. Elle a toute l’allure d’une signature à la gouache.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1164

Cette signature noire au pinceau se distingue par l’épaisseur du trait, la forme du D et surtout celle du s. On notera l’espace entre le G et le A.

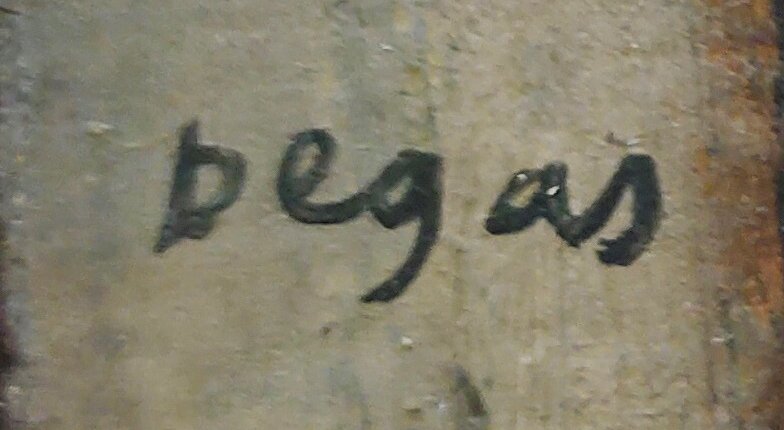

- Signé en bas droite : Degas

- Norton Simon Museum - Pasadena

- MS-587

Apposée sur un tableau au thème des repasseuses, récurrent chez Degas, cette signature partiellement érodée est d’un profil déjà connu. Elle se distingue néanmoins par la forme du D et l’effacement étonnant du e et du g.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-917

La signature de ce tableau est certainement l’une des plus originales de toutes. Elle est d’abord apposée sur la table en-dessous du bâton de lecture du journal très répandu à l’époque. Plutôt que d’être horizontale, elle suit ce dernier mais c’est surtout sa forme qu’il faut retenir. Elle est rendue par de gros traits au pinceau, chaque lettre, du D au s étant inhabituelle chez Degas. Aurait-elle été faite sur une autre œuvre, on se serait peut-être posé la question de son authenticité. Rien de tel évidemment. Cette signature permet d’écarter les clichés habituels sur l’expertise des œuvres de Degas.

- Signé en abs à gauche : Degas

- National Gallery of Art - Washington

- MS-585

Sujet récurrent chez Degas parmi les plus belles collections publiques et privées. Signé en bas à gauche au coin de la table à repasser en brun clair comme pour s’insérer dans la tonalité générale du tableau. Comme on le remarque à travers le D, la signature est graphiquement à mi-chemin entre les signatures des peintures et celles des œuvres sur papier.

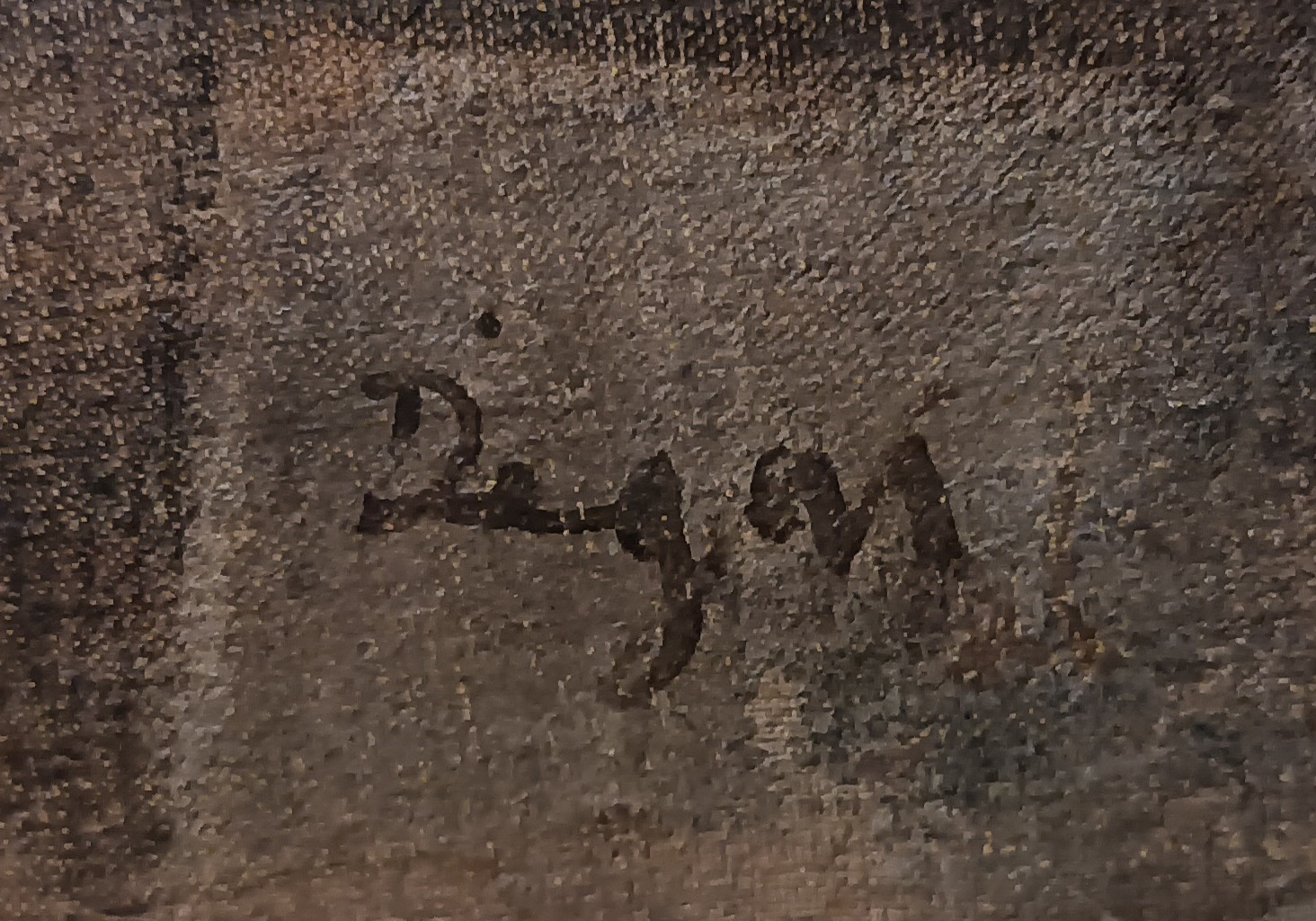

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Norton Simon Museum - Pasadena

- MS-932

C’est dans le miroir que tout se passe ici, le tableau faisant penser à une œuvre de Renoir. La signature se perd en haut à gauche, certes déchiffrable mais étrangement érodée. Degas a-t-il ainsi signé son tableau ? C’est peu probable. Il y a tout lieu de penser que la signature a subi un nettoyage invasif qui l’a ainsi transformée.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- National Gallery - Londres

- MS-1142

Un thème peu courant chez Degas, sans doute conçu lors d’un séjour en Normandie. La signature est des plus inhabituelles. Utilisant la couleur noire comme dans d’autres parties du tableau, Degas a amplifié la forme du D et l’épaisseur des lettres suivantes. La lettre D est certes la plus marquante avec son empâtement qui distingue la signature.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1249

La signature est apposée en bas à droite dans la roue du carrosse de course sur un des tableaux les plus célèbres de Degas. Elle détonne par son originalité exceptionnelle. On remarque d’abord l’épaisseur du trait noir mais aussi la formation des lettres. Est-ce un D majuscule mal formé ? Degas a-t-il voulu dessiner un D comme celui du cachet des ventes posthumes ? Le e et le g s'imbriquent étrangement. En fait il manque le bas du g qui n'apparaît pas.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-909

On reconnait aisément cette signature par sa forme régulière qu'on retrouve dans diverses œuvres, peintures, pastels mais aussi dessins. C’est évidemment la forme du D qui se rapproche de celle du cachet des ventes posthumes. La toile ressort particulièrement bien dans cette partie plus claire du tableau.

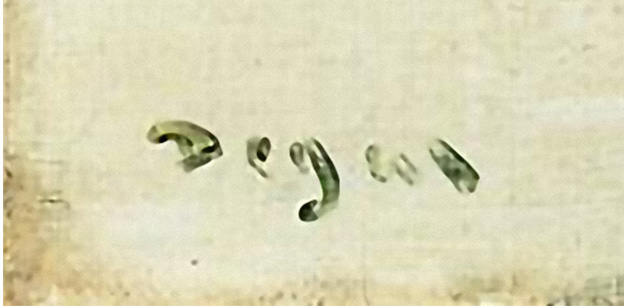

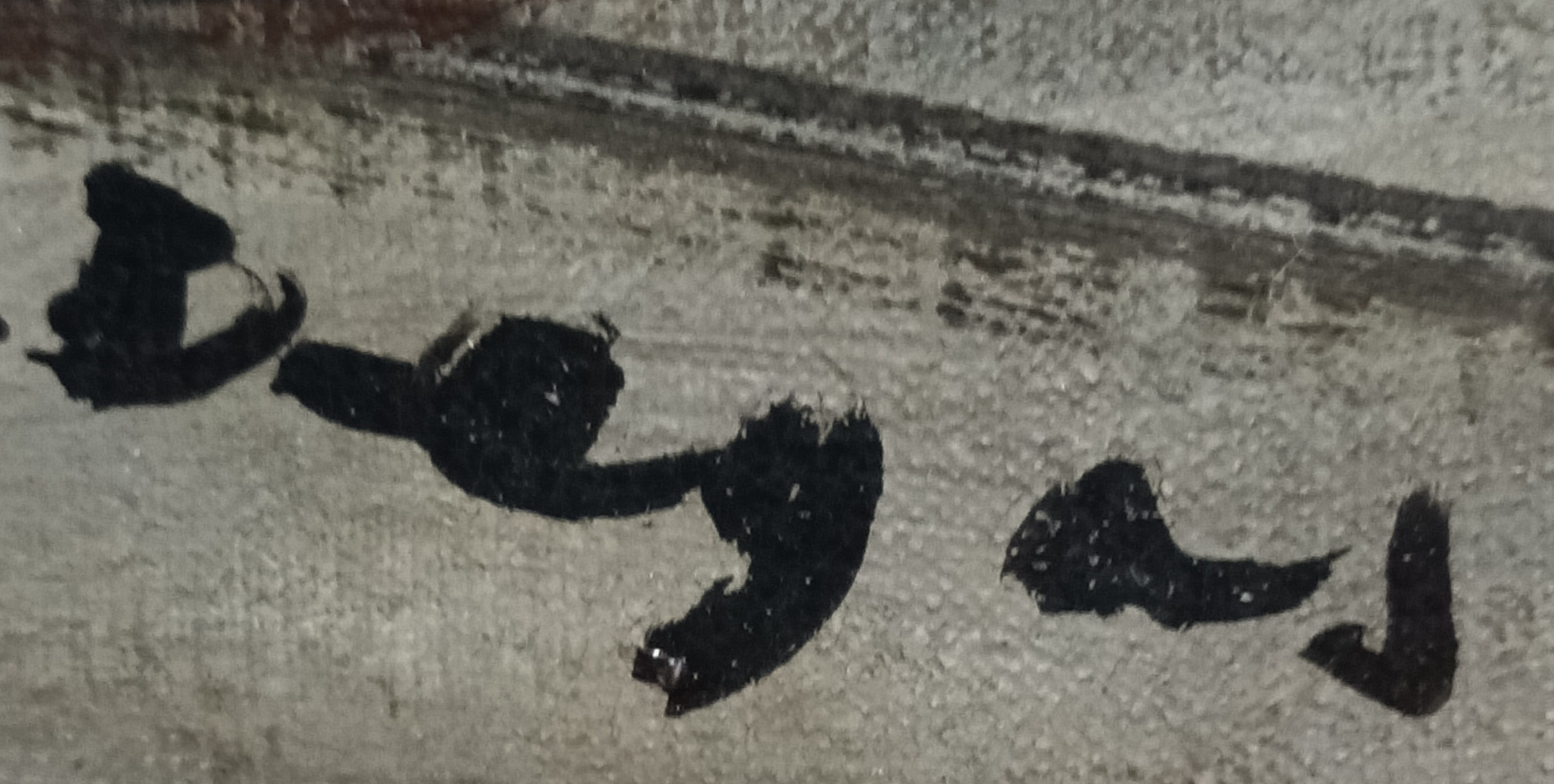

- Signé en haut à droite : Degas

- Musée Angladon - Avignon

- MS-584

La signature épouse la tonalité grise générale du tableau. Légèrement apposée en haut à droite, elle se distingue par la séparation frappante entre les lettres du nom. Les grains de la toile sous-jacente sont particulièrement bien visibles.

- Signé en bas à ngauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-244

On ne connaît pas la date exacte du tableau, ce qui explique cette datation approximative. La fiche du Metropolitan Museum of Art ne mentionne pas de signature qui existe pourtant bel et bien à gauche du tableau. Si on retient, comme c’est le cas, la date officielle des années 1882, on remarquera que la forme de la signature n’est pas nouvelle chez Degas. D’où la question de la possible évolution de ses signatures.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-576

Thème exécuté par Degas à plusieurs reprises avec des variations notamment de couleurs. Des tableaux qui figurent dans des collections publiques et privées. Sans pouvoir donner une explication logique, certaines œuvres sont signées, d’autres ne le sont pas comme au Dallas Museum of Art et quelques-unes portent le cachet des ventes posthumes. Ici, la signature est élégamment apposée, régulière et finement dessinée dont on remarquera le S. Bien que faite au pinceau sur une toile dont on voit la trame, elle fait penser aux signatures au crayon de Degas.

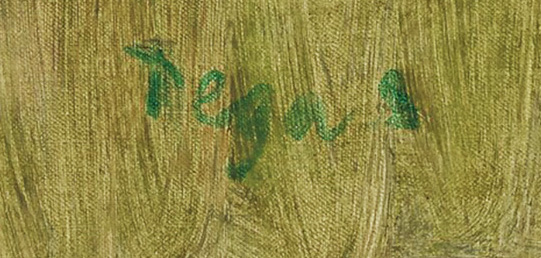

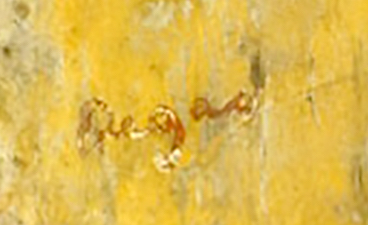

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- National Gallery of Art - Washington

- MS-1500

Degas reprend ici certains verts du tableau pour le signer discrètement en bas à droite. Une signature où l’espace entre le a et le s ne trouve pas d’explication logique. On distingue bien les touches sous-jacentes

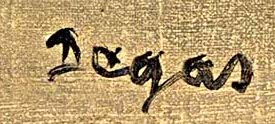

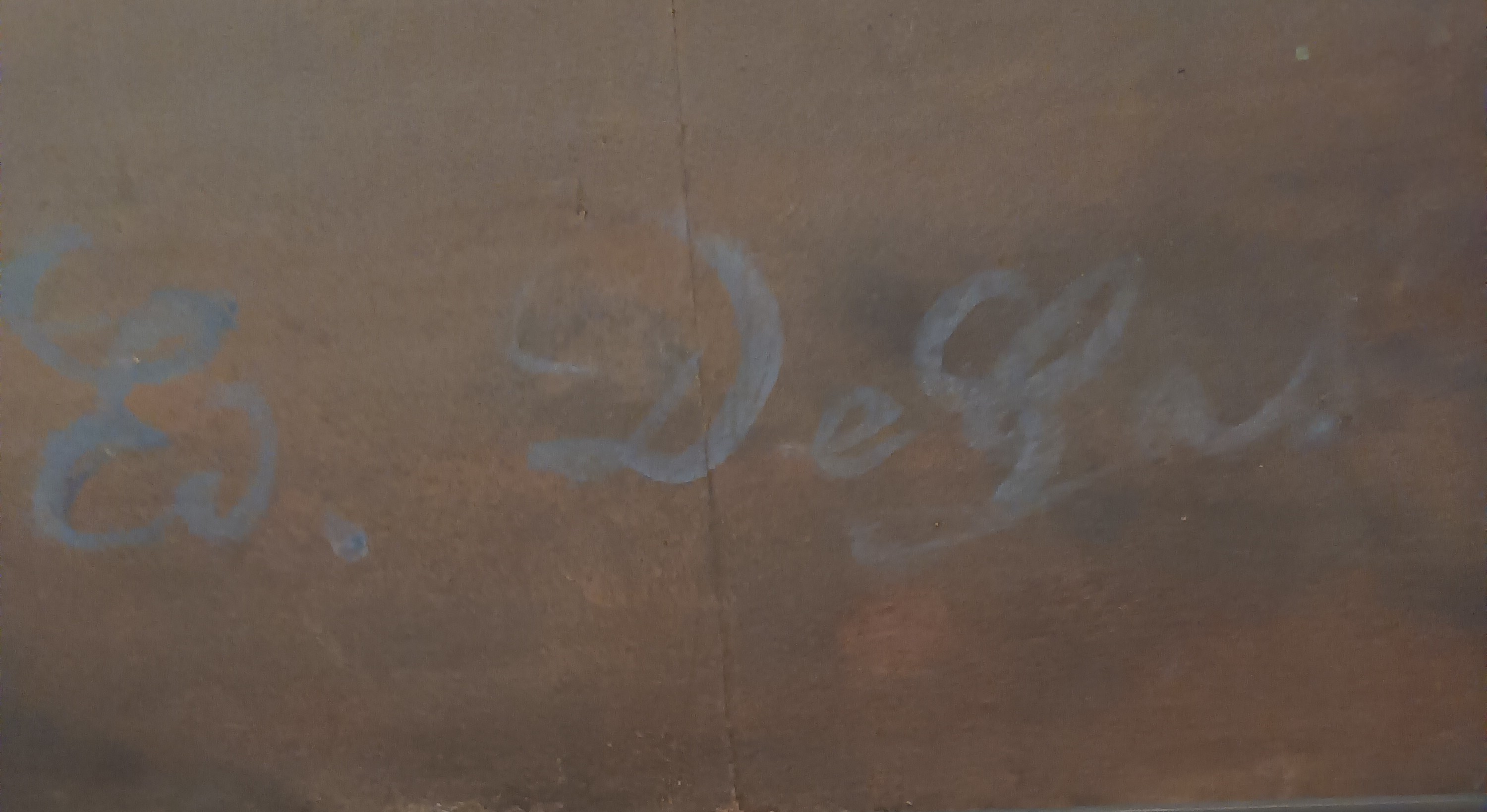

- en bas à droite : Ed. Degas

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1265

On ne connait pas chez Degas une signature aussi élégante si bien qu'on pourrait croire à un exercice de style. Chaque lettre est en effet stylisée comme si Degas avait voulu, toute proportion gardée, faire les pleins et les déliés de notre belle et ancienne écriture à la plume. On reconnaît là le E de sa carte de visite mais la forme du D est majestueuse. On remarque aussi la séparation de son nom utilisé à ses débuts avant qu'il ne fasse de Degas qu'un seul et même nom sans particule; le tableau datant de 1865.

Pastels

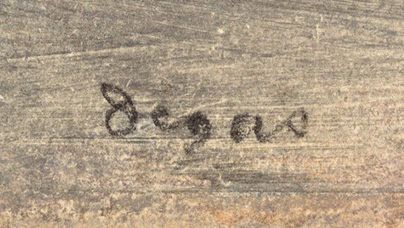

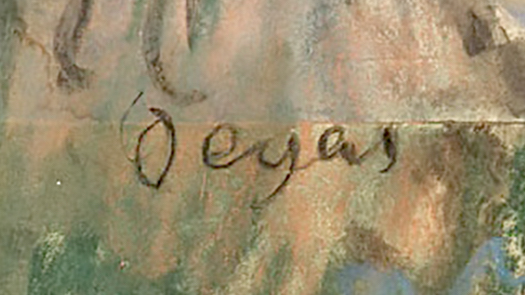

- Signé en haut à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-365

La signature a-t-elle été faite au pastel ou au crayon ? On est en droit de se poser la question tant elle est finement apposée. Ici, c’est la forme du D qui étonne évidemment. Si elle est au pastel, cette signature est particulièrement fine et discrète.

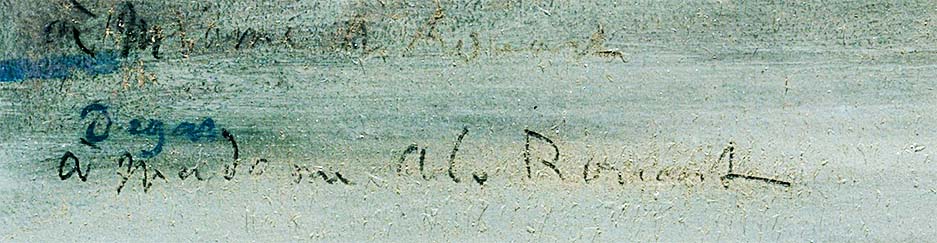

- Signé et dédicacé en bas à gauche : Degas "A Mme A

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1983

La signature est indubitablement au pastel, ce qui ne semble pas être le cas de la dédicace qui est probablement faite au crayon. Degas a sans doute repris l’ensemble puisqu’on distingue clairement une autre signature et sans doute dédicace au-dessus.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-373

Signé en blanc sans doute pour rappeler la couleur du tutu des danseuses. On remarquera la régularité de la signature et la forme habituelle du D mais surtout l’application du s. Une autre photo viendra remplacer cette photo imparfaite dès que possible.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-1366

En bas à droite dans la marge, cette signature est apposée sur une des œuvres les plus célèbres de Degas et, selon nous, l’une des plus belles. Cette série de pastels sur monotype porte Degas au sommet de son art, comparable aux œuvres de Toulouse- Lautrec, lui aussi attiré - fasciné ? - par les scènes de cabaret ou-et de café-concert. Ici, on retiendra la forme atypique du D.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-264

On retrouve cette signature au pastel en rouge assez courante chez Degas avec cette forme du D qui ne manque pas de faire penser, toute proportion gardée, au D du cachet des ventes posthumes.

- Signé en bas à gauche

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-266

La signature en noir au milieu à gauche sur la plinthe est remarquable par le caractère très inhabituel du D se terminant par une boucle rarement ainsi formée chez Degas.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-1310

Cette signature au pastel noir consacre le célèbre tableau dont le sujet reflète la passion de Degas pour l’opéra. Souvent, ce dernier laisse, comme ici, un espace après le D dont la forme est relativement peu courante.

- Signé en haut à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-221

Une variante de certaines signatures que Degas forme sur papier mais aussi sur toile. On remarquera la forme originale du D avec le retour de sa boucle.

- Signé en haut à gauche : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-447

Sans doute le mélange technique de cette œuvre - pastel et essence - a-t-il permis à Degas d’inscrire ou, pour ainsi dire, de sculpter son nom sur ce pastel. Il a très certainement utilisé le dos du manche du pinceau comme il l’aurait fait pour une huile si bien qu’on discerne le graphisme « en profondeur ». Avec sa boucle supérieure, le D est évidemment remarquable, un des seuls du genre chez Degas.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1995

Bien qu’assez courante, nous publions cette signature pour souligner les variations du D et sa régularité graphique.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-482

Cette étude est non seulement intéressante par la combinaison de plusieurs techniques - pastel, fusain, crayon et craie blanche - mais aussi par sa signature tout à fait inhabituelle pour ne pas dire au graphisme exceptionnel. Cette signature pose une pierre plus qu'intéressante sur l'expertise des œuvres de Degas.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- National Gallery of Art - Washington

- MS-405

Intéressante signature qui se rapproche du cachet des ventes posthumes de 1918 et 1919.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-566

Une variante de cette signature qu’on retrouve assez souvent dans l’œuvre de Degas, indistinctement pour les peintures et les pastels. Ici en rouge, ce qui n’est pas toujours le cas chez Degas. Bien sûr, on remarquera la forme du D et celle du g mais cette fois, c’est le s qui est particulièrement bien formé.

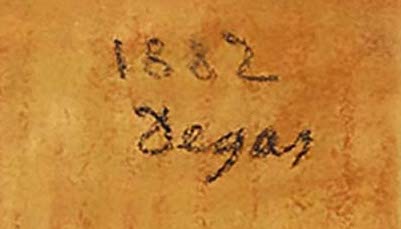

- Singé et daté en bas à droite : Degas 1882

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-561

Bien visibles en haut à droite, la signature et la date de 1882 ont été apposées au pastel sur un fond marron, une des principales tonalités de l'œuvre. La signature qui épouse une forme assez répandue chez Degas avec un D qu’on retrouve ailleurs.

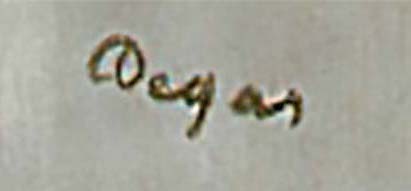

- Signé en bas au centre gauche : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-1135

La signature, probablement au pastel, est en partie effacée. On ne déchiffre que les dernières lettres, le D et le e étant à peine lisibles. On se demande quelle en est la raison sachant que le pastel autour de la signature est, lui aussi, très estompé

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-2137

Signature très certainement faite au pastel. Degas utilise une tonalité mineure - le marron - pour signer son œuvre. Elle se remarque particulièrement bien sur ce fond blanc. C'est la forme du d qui fait l'originalité de la signature et le bas du g dont Degas n'achève pas la boucle. Zoomée, la photo paraît imparfaite

.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-912

C’est sans doute l’un des plus beaux pastels de Degas signé au pastel noir sur une partie plus claire en bas à droite. Une signature qui se distingue par son D étrangement formé et l'amplitude du s.

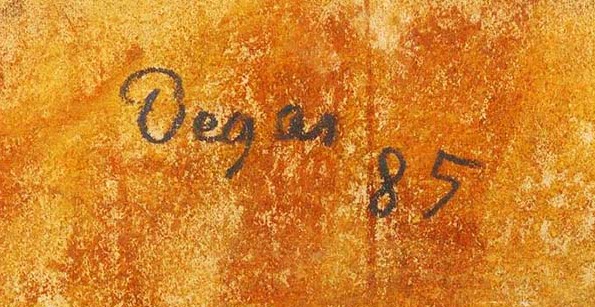

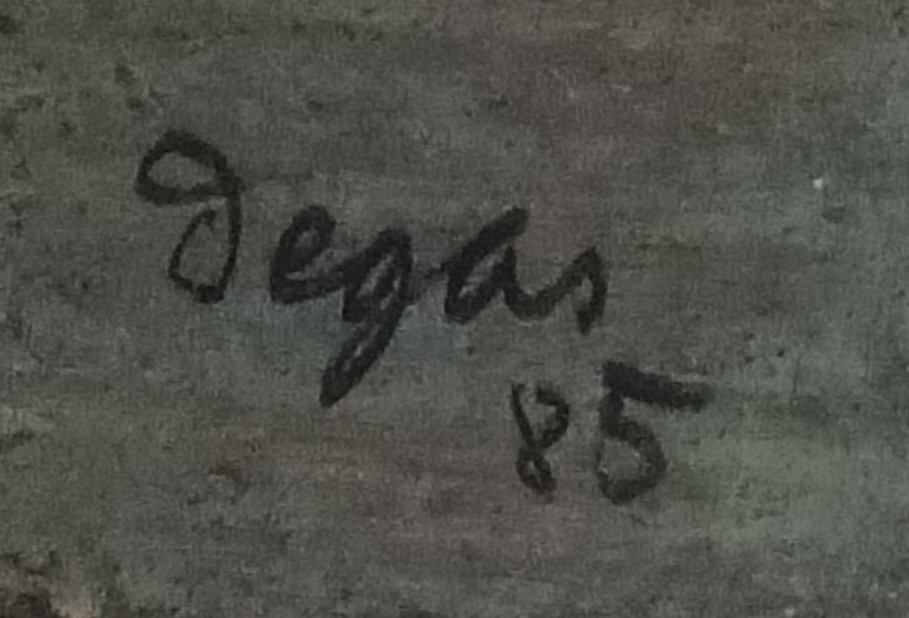

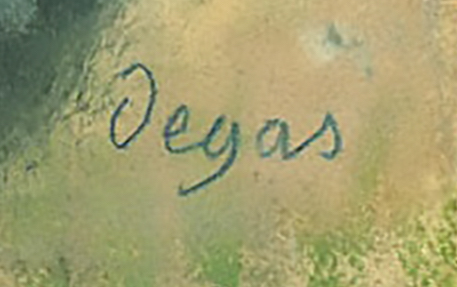

- Signé et daté en haut à gauche : Degas 85

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-996

Signée Degas et datée 85 : un document suffisamment rare pour l’inclure ici. Son graphisme ressemble néanmoins à certains autres que nous connaissons de Degas.

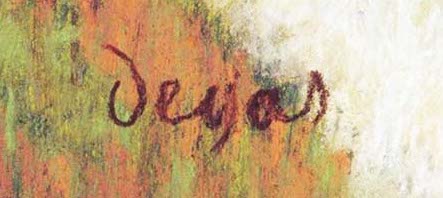

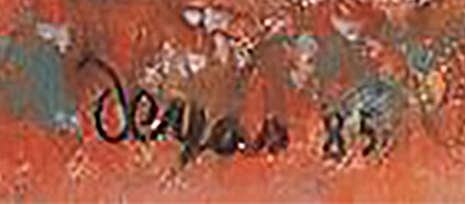

- Signé et daté en bas à gauche : Degas 85

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1219

Ici un pastel sur toile qui porte cette signature particulièrement bien dessinée. On remarquera évidemment la boucle du D et le lien entre les lettres, notamment le D et le e, que Degas sépare souvent.

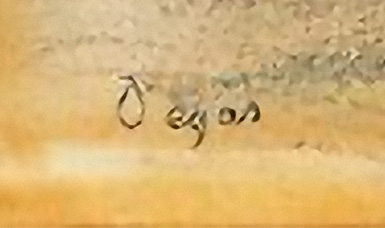

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1380

La signature est ici presque identique à celle du pastel du musée d'Orsay Le Tub, hormis la forme du d qui diffère par sa boucle. On remarquera que la signature de La Femme se peignant du Metropolitan Museum of Art a probablement été faite au pastel sec, alors que celle du musée d'Orsay au pastel gras.

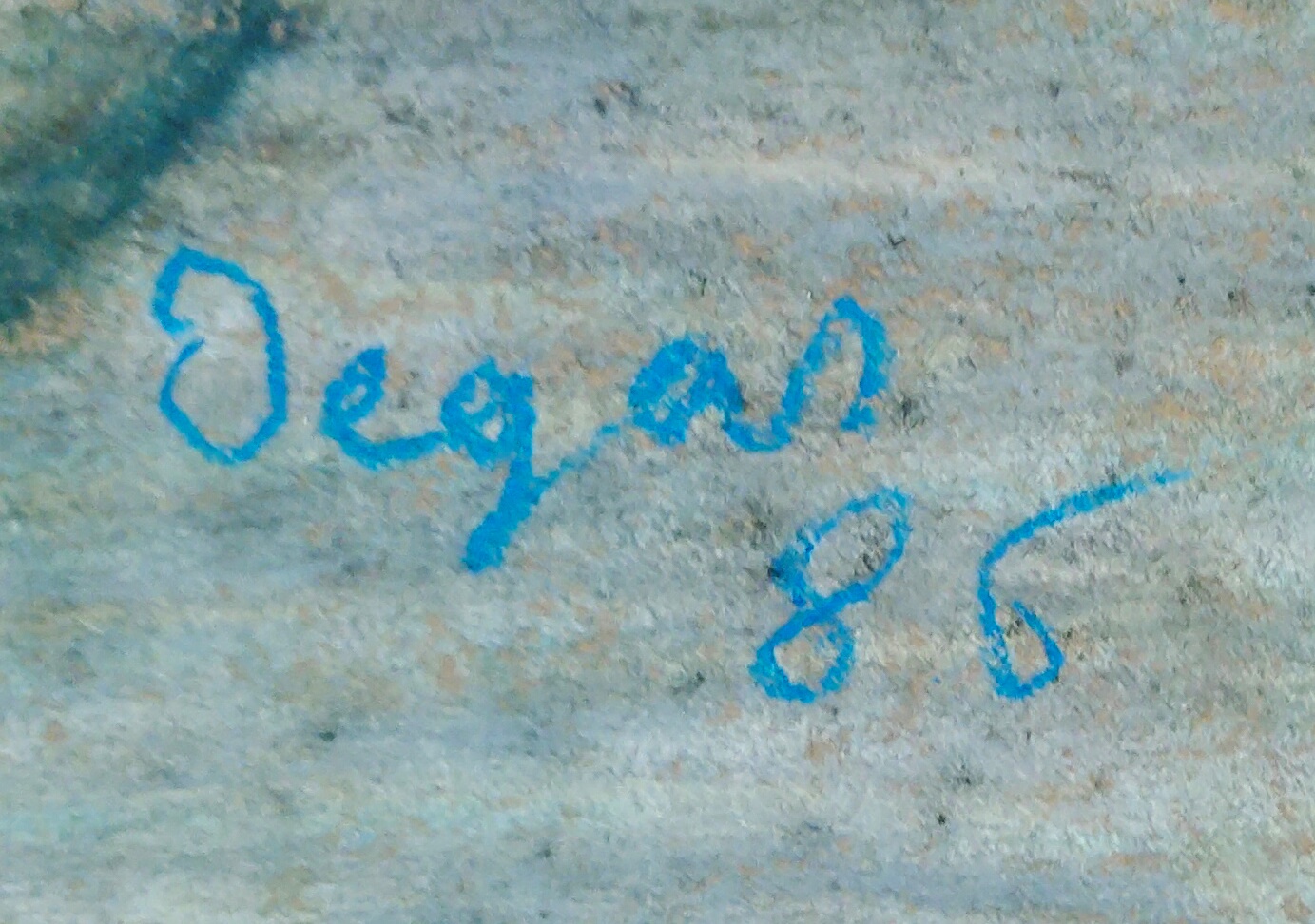

- Signé et daté en bas à droite : Degas 86

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-1252

Une signature et une date au pastel dont le bleu lumineux marque ce célèbre pastel. Le choix de cette couleur est d’autant plus surprenant qu’il ne correspond pas aux couleurs et aux tonalités dominantes de l'œuvre.

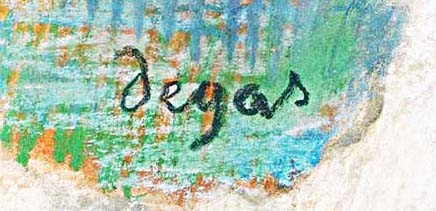

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1130

Cette signature est assez courante dans les années 1885-1890. Degas la place d’une façon originale presque au pied de la baigneuse dans un endroit bien visible. Selon le Metropolitan Museum of Art, une autre signature très estompée est apposée en bas à droite.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-976

La signature au pastel qu'on retrouve chez Degas à cette époque. Elle correspond aux tonalités générales du pastel. On constate que Degas a bien le souci de les faire correspondre, ce qui n’est pas toujours le cas avec des signatures qui tranchent avec l’ensemble du sujet.

- Signé et daté en bas à droite : Degas 85

- Norton Simon Museum - Pasadena

- MS-1035

La signature reprend le graphisme de cette époque qu’on relève sous la forme du D. Le G est étrangement inachevé. Selon le Norton Simon Museum, la date de [18] 85 aurait été ajoutée, le musée datant l’œuvre plus tardivement entre 1887 et 1890. Il est vrai que le graphisme de la date est plus raide et appliqué et qu’il ne correspond guère à celui de la signature.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-295

Signé en bas à droite sur le tronc d’arbre. On remarquera le graphisme original de la signature dont la forme très inhabituelle du D, celle du g, sans oublier le a qui ressemble plutôt à un e. La signature au pastel est ici finement apposée.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Norton Simon Miuseum - Pasadena

- MS-1574

Les pastels sur monotype sont parmi les œuvres les plus remarquables de Degas. Où a été fait ce paysage avec ses nombreux oliviers ? On peut penser à un paysage du Midi, notamment aux paysages de Monet faits à Bordighera. On remarquera l'originalité du d qui est bien séparé du reste de la signature.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-646

La signature en bas à droite se singularise par sa ressemblance avec le cachet rouge des ventes posthumes de Degas avec le D qui varie néanmois.

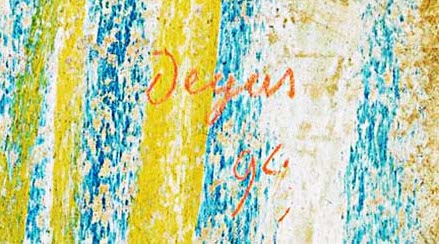

- Signé et daté en haut à droite : Degas 94

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

- MS-1061

Signé en haut à droite au pastel rouge. La signature ressort particulièrement bien sur le jaune. La date est cependant bien moins lisible. On retiendra plus volontiers la date de 1894 plutôt que celle de 1898, le 9 de la date ressemblant étrangement au g de la signature de Degas.

- Cachet vente Degas en bas à gauche

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- MS-1050

Mal apposé ou usé, ce cachet de la vente posthume peut aussi faire penser à une signature. Nous le reproduisons ici afin de souligner le potentiel d’erreur et la possible confusion entre les deux dont il faut se méfier lors d'une expertise.

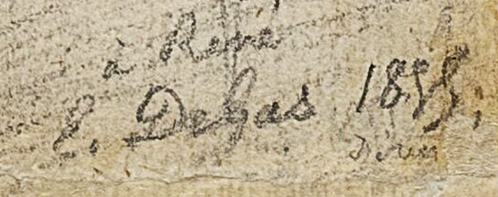

Dessins

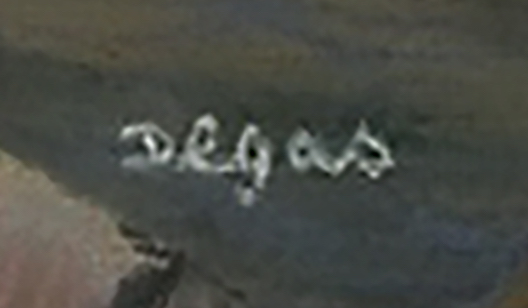

- Signé, daté et dédicacé en bas à droite : A René Ed.Degas 1855

- National Gallery of Art - Washington

Ce dessin n’est pas le seul de Degas représentant son frère à l’âge de 10 ans. Certains ne sont pas signés, d’autres comme ici, le sont et même datés et dédicacés. On trouvera intéressante cette signature dont il reprend parfois le graphisme original du e du prénom et celui du D du nom. Comme nous l’avons souligné à propos d’autres œuvres, ces formes graphiques du e et du D ont très probablement été inspirées par la carte de visite de Degas à cette époque.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

Etude pour le tableau du même nom du Metropolitan Museum of Art, ce dessin porte une signature différente de la peinture en question [MS-795]. La différence est entre la signature à l’huile et celle du dessin probablement faite au fusain. On y retrouve la forme du d déjà connue.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York

Toute l’élégance de l’œuvre repose sur le contraste entre le rose du papier et l’encre brune du dessin et de la signature. Cette dernière apposée en bas à droite doit son originalité à la forme enlevée du d. Cette dernière reprend exactement la couleur brune du dessin.

- Signé en bas à droite : Degas

- The Art Institute of Chicago

Signé au fusain de la même couleur que la tonalité générale de l’œuvre. On retrouve parfois cette même signature ailleurs parmi les peintures et les pastels.

- Signé en bas à gauche : Degas

- Institut national d'histoire de l'art - Paris

Cette signature en marge d’un monotype est l’une des plus inhabituelles de Degas. C’est évidemment la forme du D qui surprend. Il y a tout lieu de penser que la signature fut faite d’une main fébrile.

- Signé en bas à) droite : Degas

- Bibliothèque nationale de France

Les œuvres telles que les gravures et les eaux-fortes portent des signatures très inhabituelles comme c’est le cas ici avec ce D parmi les plus remarquables.

- Fusain avec reprises au pinceau et encre de Chine sur papier-calque

- Musée d'Orsay - Paris

- MS-3010

La signature de cette œuvre tardive est dans la filière des précédentes avec la forme du D très remarquable comme celle du A à travers laquelle on perçoit les hésitations de Degas. La signature ne semble pas avoir été faite d'un seul jet comme en témoigne l’espace entre le D et le e.